A Beginner's Adventures in Genetic Genealogy (a work in

progress)

by Paddy Waldron

Last updated: 29 May 2024.

Introduction

The purposes of this web page are two-fold:

- to encourage my relatives and the population at large to submit DNA samples to online

genetic genealogy databases in order to improve everybody's

chances - the chances of all genealogists and particularly of

adoptees and foundlings - of finding cousins in those databases and

proving their relationships to those cousins; and

- to explain for my own benefit, and for that of anyone else who

is interested, the basic statistical and

scientific principles behind the relatively new and

rapidly evolving science of DNA matching.

I have been advised to use a more catchy title. The first suggestion

was “A Mathematician’s Trip into His Family’s past via the Rabbit

Hole of DNA”. Other suggestions are welcome.

Why submit your DNA?

It was only after a lot of thought over a number of years that I

submitted a sample of my own DNA to FamilyTreeDNA

(FTDNA) on 20 October 2013, receiving the results on 15 November

2013.

At the time, FamilyTreeDNA was really the only practical and

affordable option for those residing outside the United States of

America, where the first three big DNA companies were based. The

alternatives at the time were AncestryDNA

and 23andMe.

The basic selfish reasons that motivate most people to submit DNA

samples to a genetic genealogy database are to confirm their own

genealogical relationships and to find their own long lost

cousins.

However, you should consider submitting your DNA not just for

your own benefit, but for the benefit of others, including those

only distantly related to you. You can rest assured that your own

descendants will be literally eternally grateful to you for doing

so. It is much cheaper and easier to do it now than for your

survivors to do it when you are dead. Even if submitting your

DNA doesn't help you directly, you might have the missing jigsaw

pieces that will solve someone else's mystery. Genetic

genealogy databases are of particular value to those who don't

know much about their biological ancestry due to adoption,

abandonment, infidelity, sperm or egg donation and similar causes.

The value of an online genetic genealogy database to those

searching for relatives depends fundamentally on the number of

people in the database. The first to join do need to make a leap

of faith and exercise patience until the database reaches critical

mass. When you do join, there are huge positive externalities for

those already in the database and also for those who join

subsequently. If your close relatives are not in the database,

then you cannot be matched with them. If your close relatives are

already in the database, then by joining you are presenting them

with a valuable and much appreciated gift.

The first three major genetic genealogy companies were all based

in the USA and some either do not welcome DNA samples from outside

the USA or have a pricing policy designed to rip off those

resident outside the USA. For those whose roots are in the USA,

the databases were already approaching critical mass by 2014.

Critical mass for those in countries like Ireland, where I live,

was much further off when I submitted my sample. Someone has to

get the ball rolling, so why not you? If members of your extended

family (like all families in Ireland) emigrated to the USA, then

you already have a good chance of finding their descendants. And

you may even find cousins among the early participants from other

jurisdictions. Or you may just help distant relatives without a

well documented family tree to focus their searches in the correct

direction, whether that is on your own branch of the family or on

another branch of the family.

On the other hand, if there is a family secret that you, or

others in your family, would like to remain a secret, then genetic

genealogy may not be for you. Conversely, if you feel that now is

the time to bring the family secret into the open and obtain

closure for all involved, then genetic genealogy is definitely the

way to go.

Genetic genealogy can also reveal family secrets that nobody ever

suspected, for example an inadvertent baby swap at Fordham

Hospital in The Bronx in 1913 which went unnoticed for over a

century.

In fact, a disproportionate number of those resorting to DNA to

trace their family history are adoptees, or parents or descendants

of adoptees, or even foundlings with no paper trail at all on

their biological family. I will do my best to assist and advise

any such people among my own DNA matches, insofar as this is

possible without putting unwanted pressure on those on the other

side of the family secret who may want to keep it a secret. Doing

my best includes encouraging all my relatives to submit DNA

samples to one of the DNA companies so that I will be able to tell

those with matching DNA and no paper trail as precisely as

possible on which side of my ancestry they are likely to be

related to me.

I also have my own, possibly selfish, reasons for wanting my own

relatives to join a genetic genealogy database. Having submitted

my own DNA, I now want to compare my results with those of:

- known relatives whose precise genealogical relationship

to me is proven;

- probable relatives whom I know personally and with whom

I suspect that I have a genealogical relationship, still

unproven; and

- possible relatives whom I do not know personally but

whose DNA results suggest that there is a significant

probability, small or large, that we have a genealogical

relationship, close or distant, but also unproven.

If you are reading this, then there is a fair chance that you are

already in one of these categories, so please read on! Even if you

have no reason to suspect that you are closely related to me, I

hope that what follows will help your understanding of what you

can learn from your own DNA results.

If you belong to one of the first two categories and you have

already submitted a sample of your DNA to one of the DNA

companies, then please get in touch so that we can compare

results. If you belong to the third category, then we will be

automatically put in touch through either the databases maintained

by the DNA companies or a third party database like GEDmatch.com (to which you

should copy your results right now, if you have not already done

so). However, if you have not published the information that you

already have on the relevant website, or explained in your profile

why you have not done this, then I will assume that you are not

sufficiently interested in your ancestry to want to correspond

further with me.

To be a successful genealogist, you must record what you know of

your relatives in a good software package, offline (preferably) or

online (if you have very fast broadband and more faith than I do

in cloud computing, and trust your online service provider and

your cloud data not to evaporate, as my Vodafone e-mail,

mundia.com messages, etc., have done). I use Ancestral

Quest. All good genealogy software packages will export

selected information, typically just names, dates and places for

your direct ancestors, to a GEDCOM file (a standardised format for

exchange of genealogical data) which can be uploaded to the

relevant DNA website. When a FamilyTreeDNA customer uploads a

GEDCOM file, the list of ancestral surnames on the FamilyTreeDNA

profile is automatically populated, but the names of your most

distant known patrilineal and matrilineal ancestors must be

entered separately. You must also link the DNA sample to the

correct individual in the family tree. I have a seen a few cases

of DNA data purporting to be from an individual who has been dead

for hundreds of years, something that is not yet commercially

available. If the family genealogist persuades you to provide a

DNA sample, he or she should be able in return to provide a GEDCOM

file to go with it, although it may initially cover only your

shared ancestors. I have written much more about this here.

At GEDmatch.com, multiple DNA samples can be linked to a single

e-mail address and a single GEDCOM file.

I recognise that there are conflicting opinions on how much

detail adoptees should include on their FamilyTreeDNA profiles;

the onus is on those who choose to leave their profiles blank to

initiate contact with all their possible relatives. My general

guidance for those aiming to reunite families separated by

adoption, whether using DNA or more conventional methods, is not

to rush in without the advice

of an experienced genetic genealogist and/or an

experienced social worker, as there will only be one

chance to make the critical first contact a success.

If you are one of my known or probable relatives and you have not

yet submitted a DNA sample to one of the DNA companies, then

please consider doing so.

As of 7 June 2018, the two best

initial options are:

- For USD69 [Father's Day sale price] plus taxes plus shipping

plus a possible surcharge for ordering from outside the U.S. or

having a non-U.S. address plus recurring annual membership fees,

use AncestryDNA.com; or

- For a one off payment of USD79 [regular price] or USD59

[Father's Day sale price] plus shipping, use Family Finder which

can be ordered from https://www.familytreedna.com/family-finder-compare.aspx#/shoppingCart?pid=215

Other

websites may provide more up-to-date pricing information.

FamilyTreeDNA is clearly less expensive, particularly for those

outside the USA and for those not already paying annual membership

fees to ancestry.com. FamilyTreeDNA also has the advantage of

geographic and surname projects and Y-DNA and mitochondrial DNA

products. However, AncestryDNA has a much bigger customer

base (over 5 million as of August 2017, about five

times the size of FTDNA, but representing only 30 countries as of October

2016) and will probably find you more relatives. The choice

is yours. If you choose AncestryDNA, you can still join the

FamilyTreeDNA database via the free autosomal transfer. However, you will

need to send a second sample direct to FamilyTreeDNA for Y-DNA or

mitochondrial DNA analysis.

There are a growing number of DNA comparison websites and those

interested in finding long-lost relatives should be in all of

them. While helping an adoptee who is married to a Murphy, I

coined what I have called Murphy's Law of Genetic Genealogy:

If there are N DNA comparison websites and your DNA is

in N-1 of them, then your most important match will be in the Nth.

In the words of another widely used metaphor, there are many

online gene pools out there and there are many people who are in

only one or two of them; for maximum effect, you must fish in all

of these pools.

I strongly urge all those who have sent DNA samples to

AncestryDNA and those who sent DNA samples to 23andMe between

November 2010 and August 2017 to transfer their autosomal DNA data to

FamilyTreeDNA.com if they do not already have a Family Finder

presence. You may find new long lost relatives who have sent

their DNA to FamilyTreeDNA but have not yet transferred their data

to GEDmatch.com. This free service was announced on 16 February

2017.

If you have used FamilyTreeDNA for Y-DNA or mitochondrial DNA but

used one of the other companies for autosomal DNA, then this

advice also applies to you.

Before May 2016 (see here), AncestryDNA and FamilyTreeDNA used

the same set of autosomal SNPs, so importing AncestryDNA data to

the FamilyTreeDNA database and running comparisons was

straightforward. After AncestryDNA changed to a different and

smaller set of autosomal SNPs, it took nine months to develop a

new matching algorithm.

Whichever DNA company you use, you can copy your results file to www.gedmatch.com

for free to compare with people who have used the other lab (or

23andMe.com, which is a poor third from a genealogical

perspective).

End-of-year sales have become an annual tradition in the world

of genetic genealogy. For the end-of-2013 sale, a USD100

restaurant.com gift card and Family Finder Testing together cost

only USD99, so those living in the USA who like eating out could

actually profit by USD1 by submitting DNA samples! While this

particular offer is unlikely to be repeated, keep an eye out for

other special offers. Prices are also traditionally cut around DNA

Day (25 April), Mother's Day in the United States (the

second Sunday of May) and Father's Day in the United States (the

third Sunday of June).

The more remote our known connection, the more interesting I

think the results will be.

On my paternal side, I am naturally

interested in exploring the various origins of the Waldron surname

in Ireland. If you are a male Waldron with Irish roots, I

particularly urge you to please consider purchasing a

kit! In this case, I initially recommend not Family Finder

Testing but the Y-DNA37, Y-DNA67, Y-DNA111 or Big Y-700 products,

whichever suits your budget. I would love to see some other Irish

Waldron ancestors listed in the Paternal Ancestor Name column on The

WALDRON

Surname DNA Project - Y-DNA Colorized Chart (where I am kit

number 310654). If you are a male Waldron and are already a

FamilyTreeDNA customer, please click the Join Request link on this page to join the

project. My genealogical research has been stuck for many decades

at my GGgrandfather Thomas Waldron (c1825/6 Roscommon-1902

Limerick). I would love to find a Waldron Y-DNA match to give me

some idea where I should be looking in order to go back another

generation. Likewise, I would love to find more Irish Waldron

Y-DNA non-matches in order to rule out some of the wild goose

chases on which I have gone over the years.

Also on my paternal side, I am particularly interested in

exploring my relationship to a number of reputed fifth cousins,

whom I know about from notes in my County Clare grandmother's

diaries and in her letters about meetings with various sets of her

third cousins. In particular, these include the Nolans of Kilkee,

the Houlihans of Killard, the Burkes of Cloonnagarnaun and their

apparent descendants the O'Maras and O'Connells of Moveen. While

the family friendship with all of these families remains strong

down to the present day, nobody remembers any longer who our

common ancestors were, and furthermore the genealogical records

which might unlock these secrets have not survived. There are also

the Clancys of Cranny who remained the closest of friends with the

Clancys of Killard (one of whom was my greatgrandmother) long

after the details of their relationship were forgotten. If you

belong to one of these families, I particularly urge you to please

consider purchasing

a

kit and ordering Family Finder Testing! I also encourage all

Clancys to order Y-DNA analysis. If you have any ancestors from

any part of County Clare, then as soon as you get a password for

your FTDNA kit, I recommend that you visit the Clare

Roots project Activity Feed and hit the JOIN button at the

top right. (Disclaimer: I am Administrator of this project.

Project administrators can see your DNA results when you join

their projects and can help you to interpret them.)

Finally on my paternal side, DNA helped to confirm the relationship between the

Blackalls and Clancys of Killard in County Clare.

Similarly, on my maternal

side, I am particularly interested in exploring whether my

grandparents (both Durkans by birth) or my grandfather's

parents (also both Durkans by birth) might have been related other

than by marriage. Both couples lived in the townland of Cuilmore

(the one in the civil parish of Kilconduff in County Mayo). I

would also like to explore how my mother was related to her "Aunt

Ellie" McDonagh, who clearly wasn't a genealogical aunt, but did

have a Durkan grandmother. Aunt Ellie was from the townland of

Cuillalea in County Mayo, from an area apparently known locally as

Cartoonbawn or Cortoonbawn or Cortoon Bawn or Ballincurry or

Ballinacurry, or however you would like to spell it yourself. If

you are connected to the Durkans or to the McDonaghs, please

consider purchasing

a

kit and ordering Family Finder Testing! [Sending my DNA to

AncestryDNA in 2015 threw up a critical clue

in the "Aunt Ellie" mystery.] I am not yet aware of a County Mayo

project at FTDNA, but would love to see one started.

If you descend from any of these families and have already

submitted a DNA sample, then please copy your raw data to

GEDmatch.com and let me know your GEDmatch kit number; mine is

VA864386C1. I am aware of at least one Nolan descendant and of

several Houlihan descendants who have submitted DNA samples but

have not yet sent me a GEDmatch kit number.

On all sides, for reasons which will become clear as you read on,

I would like to have the DNA of at least eight third cousins

available for comparison, at least one of them descended from each

pair of my greatgreatgrandparents.

I have prepared this web page in an effort to help my known and

probable and possible relatives, and anyone else who is

interested, to understand the rapidly evolving, but often poorly

explained and poorly understood, discipline of genetic

genealogy. It may even be of help to the service providers

struggling to help their customers to make their way more easily

up the steep learning curve that I have experienced in my own

adventures in genetic genealogy. I certainly hope that it will

help customers and FamilyTreeDNA itself respectively to get more

out of the FamilyTreeDNA.com website

and to fix some of its shortcomings.

If you fall into one of the categories of my known, probable or

possible relatives and would like to consult my password-protected

online family tree, please read on or scroll down to the end of

this web page for details of how to obtain a password.

Some people are reluctant to submit DNA samples to commercial

organisations and/or to submit the resulting raw data to third

party DNA-comparison websites and/or to publish kit numbers which

would allow strangers to do one-to-one DNA comparisons, often for

reasons that they cannot articulate. For example, one person considered it a bad idea to

publish GEDmatch kit numbers in a closed facebook.com group with

only 2,824 members, monitored by a handful of administrators of

great integrity. Any information posted in such a group is

far less public than information that is posted at GEDmatch.com

itself, where the audience is orders of magnitude larger and

registration is automated and not monitored. All

GEDmatch.com users have already happily handed over their actual

DNA to a commercial organisation and handed over all the raw data

extracted from it by the commercial organisation to GEDmatch, so

there is no reason to think that merely giving the kit number in a

closed facebook group is a bad idea. Of course, DNA may

reveal unknown or unsuspected relationships, but GEDmatch.com

users must have been aware of that before sending off their

samples, and we cannot change history. Those whose genetic

ancestry has been concealed from them have a right, and usually a

great desire, to know it.

The genetic locations examined for genealogical purposes are

generally not the same as the genetic locations that have been

examined for evidence of possibly elevated risk of certain

diseases. It is widely believed that some individuals have "good

genes" and are likely to live longer, and other individuals have

"bad genes" and are likely to suffer more ill health. The margins

of error associated with health predictions derived from DNA are

just as hard to find, and probably just as large, as the margins

of error associated with the estimated ethnicity percentages

derived from DNA and peddled by many DNA companies.

Revealing to insurers and financiers that one has good genes is

likely to make one's health care less expensive and one's pensions

more expensive, and conversely revealing that one has bad genes is

likely to make one's pensions less expensive and one's health care

more expensive. If an insurance company got its hands on one's raw

data (which it certainly wont do merely by knowing the

GEDmatch.com kit number), it might wish to reduce premiums for

illness and death insurance, as I call them, and increase premiums

for pensions, or vice versa. (The marketing people call these

products health and life insurance, but somehow still market fire

and theft insurance!) In many jurisdictions (certainly in

the U.S.), law prohibits insurance companies from charging higher

premiums to those whose bad genes put them at higher-than-average

risk of certain diseases. This is referred to as

"non-discrimination", although the law actually discriminates

against those whose good genes put them at lower-than-average risk

of the same diseases, by forcing them to pay the same as if they

were at average risk.

Others worry that DNA samples sent to genetic genealogy companies

may be used, with or without search warrants, to identify them or

their close or distant relatives as suspects for criminal

offences. Those of us who are not criminals need not worry about

our DNA being used to convict us of crime. Those who don't trust

the courts and juries to see reasonable doubts in DNA evidence

probably don't trust courts and juries to process other types of

evidence fairly either. The DNA locations used to uniquely

identify criminal suspects beyond reasonable doubt are the

fastest-mutating locations, large numbers of which are unlikely to

be the same for any two individuals bar identical twins. The DNA

locations used to identify closely related individuals are

slower-mutating locations, which are very likely to be the same

for those who are closely related.

This long introduction may have raised lots of questions in the

minds of readers. Please read on for the answers to those

questions.

Statistical

and Scientific Principles

Table of contents

[The text of these chapters still needs to be embellished with

many more illustrations, which I might have to borrow from someone

like Maurice Gleeson!]

Other internal links:

Thoughts and questions on DNA, sampling, testing and marketing

Background

Having been increasingly addicted to genealogy from the age of 12

or earlier and having a degree in mathematical sciences with a

particular interest in probability and statistics, it was

inevitable that I would develop an interest in DNA and in genetic

genealogy.

I attended various one-off lectures on these subjects over a

number of years, and read lots of explanations, often ending up

more confused rather than less confused after an effort to improve

my understanding. I have still not found the inspirational book or

inspirational teacher that suddenly fits everything into place

within the context of my prior knowledge, such as happened with

probability and statistics when I took Adrian Raftery's course

(251) as a third year undergraduate at Trinity College Dublin back in

1983/4. (In the genetic genealogy field, my brief exposure to

lectures by Maurice

Gleeson and Dan Bradley has, however, helped a lot.)

The more I have read, the more sceptical I have become about the

lack of scientific and statistical rigour in genetic genealogy and

about some of the inferences apparently drawn from DNA evidence,

to the extent that I considered entitling this web page "A

Sceptic's Adventures in Genetic Genealogy". Then I discovered that

there is an ongoing

debate about whether the second letter of sceptic should be

a C or a K and whether the spelling difference reflects a slight

nuance in the meaning of the word rather than merely the side of

the Atlantic Ocean on which I grew up! When I was publicly accused

of being a DNA "Luddite", I thought I should perhaps put that word

in the title, or perhaps just admit to being "confused", but I

eventually settled for the more neutral "beginner".

My scepticism made me reluctant to submit my DNA for analysis,

and I continue to exercise caution rather than jump to unwarranted

conclusions on the basis of sloppy statistical analysis, sloppy

science and sloppy explanations, all of which I still believe are

typical of the DNA industry.

On the third day of the joint Back To Our Past (BTOP)

and Genetic

Genealogy Ireland 2013 shows at the Royal Dublin Society (20 Oct 2013), Kathy Borges

of the International

Society of Genetic Genealogists (ISOGG) eventually did

persuade me to purchase Y-DNA and autosomal DNA products from

Family Tree DNA. Notification arrived by e-mail that my autosomal

DNA results were available online on 16 Nov 2013 and that my Y-DNA

results were available online on 21 Nov 2013.

I should probably try to weave my initial thoughts and the

answers that I have found to my questions into the ISOGG Wiki,

but for now I still have more questions than answers and it is

much quicker and easier to post them all together here on this

single web page on my own personal web site documenting my own

adventures as a sceptic in genetic genealogy.

Perhaps I should go and study the subject formally somewhere like

The

Mathematical Genetics Group at the University of Oxford.

I hope that this chapter will help to dispel

some myths, in particular about the need for a little jargon, and that the next chapter will get me some feedback

about interpreting my own autosomal DNA

results, or lack thereof. To begin with, however, some

definitions will help to add some rigour.

Definitions

Basics

My good friend Kevin O'Brien summarised the difficulties of DNA

research succinctly in one sentence:

"This DNA research is different from tracing and is more like

geometry as you are given the answer and then you have to prove

the theorem."

To prove the theorems, one must understand a few

essential

basic

concepts.

If you are reading this page, you hopefully have some basic

understanding of DNA and of genetic genealogy. For those who

don't, I had better begin by outlining some basic definitions.

DNA (short for deoxyribonucleic acid) is material

contained within human cells (and the cells of any living

organism) and inherited by children from their parents. Genetic

genealogy is the use of variations in DNA between

individuals in order to assist genealogical research. For the

purposes of genetic genealogy, DNA is represented by long strings

of the letters A, C, G and T, for example ACCTGAGTCAGTAC. As far

as genetic genealogy is concerned, the precise details of the

chemical structures which these four letters represent are

unimportant. (If you must know, they are initials representing the

four bases adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G) and thymine

(T).)

As an occasional computer programmer, I like to describe

something like ACCTGAGTCAGTAC as a string of letters and

something like GTCAGT as a substring of ACCTGAGTCAGTAC.

The words sequence and subsequence may be used by

others as synonyms of string and substring.

A person's genome is the very long string containing his

or her complete complement of DNA. For the purposes of genetic

genealogy, various shorter strings from within the genome will be

of greater relevance. These shorter strings include, for example,

chromosomes, segments and short tandem repeats (STRs).

The human genome is made up, inter alia, of 46 chromosomes.

The FTDNA

glossary (faq

id:

684) defines a DNA segment as "any continuous run or

length of DNA" "described by the place where it starts and the

place where it stops". In other words, a DNA segment runs from one

location (or locus) on the genome to another

location. For example, the segment on chromosome 1 starting at

location 117,139,047 and ending at location 145,233,773 is

represented by a long string of 28,094,727 letters (including both

endpoints).

For simplicity, I will refer to the value observed at each

location (A, C, G or T) as a letter; others may use

various equivalent technical terms such as allele, nucleotide

or base instead of 'letter'.

The FTDNA glossary does not define the word block, but

FTDNA appears to use this word frequently on its website merely as

a synonym of segment.

A short tandem repeat (STR) is a string of letters

consisting of the same short substring repeated several times, for

example CCTGCCTGCCTGCCTGCCTGCCTGCCTG is CCTG repeated seven times.

A gene is any short segment associated with some physical

characteristic, but is generally too short to be of any great use

or significance in genetic genealogy.

Every random variable

has an expected value or

expectation which is the

average value that it takes in a large number of repeated

experiments. For example, if an unbiased coin is tossed 100 times,

the expected value of the proportion of heads is 50%. Similarly,

if a person has many grandchildren, then the expected value of the

proportion of the grandparent's autosomal DNA inherited by each

grandchild is 25%. Just as one coin toss does not result in

exactly half a head, one grandchild will not inherit exactly 25%

from every grandparent, but may inherit slightly more from two and

correspondingly less from the other two.

There are four main types of DNA, which each have very different

inheritance paths, and which I will discuss in four separate

chapters later:

- Y-DNA

- A human being's 46 chromosomes include two sex chromosomes.

Males have one Y chromosome containing Y-DNA and

one X chromosome containing X-DNA. Females have

two X chromosomes, but do not have a Y chromosome. Y-DNA is

inherited patrilineally

by sons from their fathers, their fathers' fathers, and so on,

"back to Adam". (Most geneticists are not creationists, but the

concept of "Adam" is still useful and used. However, there is a

subtle difference. The "biblical

Adam" was the first and only male in the world at the

time of creation. The "genetic

Adam", the most recent common patrilineal ancestor of

all men alive today, was merely the only male in the world in

his day whose male line

descendants have not yet died out. There were almost

certainly many other males alive at the same time as genetic

Adam who have no male line descendants alive today. Just think

through the men in your grandparents' or greatgrandparents'

generation to get a feel for how precarious the survival of the

male line is through even a handful of generations. Or think of

the surnames of your distant ancestors which no longer survive

as surnames of your living cousins.)

Some people are actually confused by the simple concept that

Y-DNA follows the male line, and even by the simpler concept

that in most cultures the surname follows the same male line. If

you belong to (or join) the relevant facebook groups, you can

read about examples of this confusion in discussions in the County

Clare

Ireland Genealogy group, the County

Roscommon,

Ireland Genealogy group and The

Waldron

Clan Association group. Another interesting

discussion concerns whether those confused by poor

explanations about the inheritance path of Y-DNA are more likely

to be those who don't themselves have a Y chromosome!

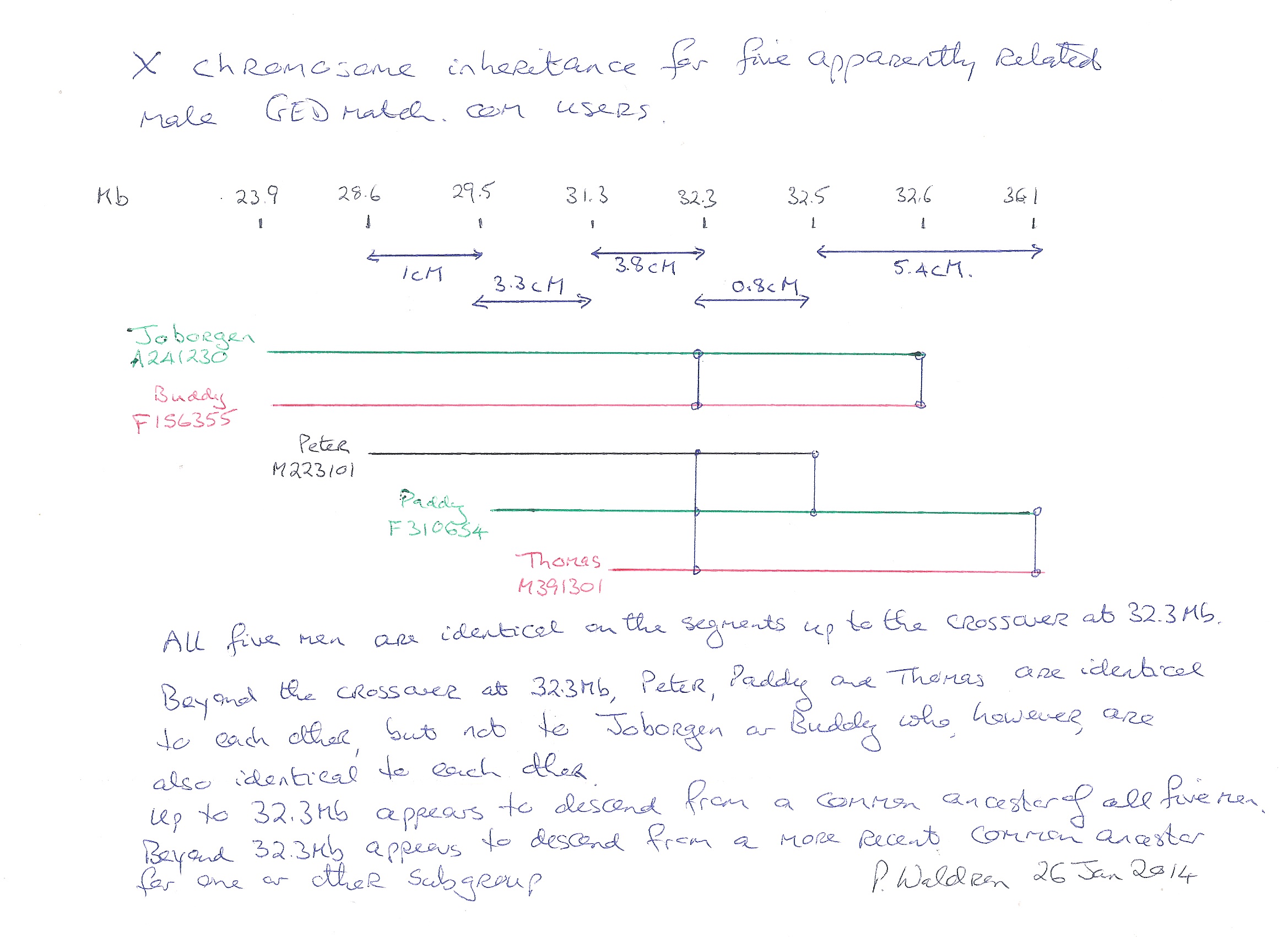

- X-DNA

- Every male inherits his single X chromosome from his mother.

Every female inherits two X chromosomes, one each from her

father and from her mother. The X chromsome inherited from the

mother is usually further broken down, because it is one of the

chromosomes subject to the random process of recombination,

into smaller segments represented by shorter strings of A, C, G

and T. In this context, recombination is the process by which

the X chromosome inherited from the mother crosses over randomly

along its length from being a copy of that inherited by the

mother from the maternal grandfather to being a copy of that

inherited by the mother from the maternal grandmother or vice

versa. Thus, the segments in the X chromosomes which everyone

inherits from his or her mother are expected to come equally

from both maternal grandparents. The recombination process is

sometimes described as being analogous to shuffling two packs of

playing cards and splitting the combined pack into two equal

halves. Going back another generation, the segments in the X

chromosome which every woman inherits in its entirety from her

father are expected to have originally come equally from two

greatgrandparents, her father's maternal grandparents. While the

average or expected breakdown between the relevant paternal and

maternal sources is 50:50, we will see later than the observed

breakdown can be anywhere between 0:100 and 100:0.

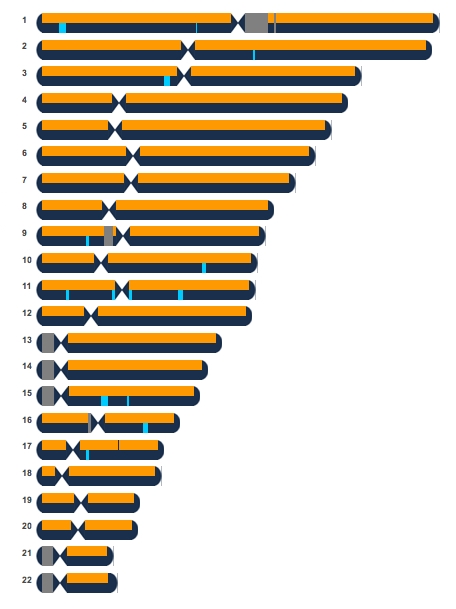

- Autosomal DNA

- Autosomal DNA (or atDNA for short) is inherited by everyone in

the other 22 pairs of chromosomes which are not sex chromosomes.

These autosomal chromosomes are often referred to for

short as autosomes and are numbered from 1 (the longest)

to 22 (the shortest). One chromosome in each pair comes from the

father and the other from the mother. Just like the maternal X

chromosome, all 44 of these chromosomes are subject to

recombination, which means that the segments in each of the 22

paternal chromosomes are expected to come equally from both

paternal grandparents, and those in each of the 22 maternal

chromosomes likewise are expected to come equally from both

maternal grandparents.

- Because of recombination, segments come ultimately from all

ancestors in recent generations, but those large enough to be of

genealogical value can be traced back to a vanishingly small

proportion of the exponentially increasing number of ancestors

in earlier generations.

- "Genealogical value" is not something that can be precisely

defined, but it will be argued below that autosomal DNA contains

a few hundred segments of genealogical value per individual.

- mtDNA

- The nucleus of every human cell contains 23 pairs of

chromosomes, comprising 22 pairs of autosomal chromosomes and

one pair of sex chromosomes. Outside the nucleus, every human

cell also contains mitochondrial DNA (or mtDNA for short).

Similarly to the patrilineal inheritance of Y-DNA from male to

male along the direct male line, mtDNA is inherited matrilineally,

but by both sons and daughters along the direct female line,

from their mothers, their mothers' mothers, and so on, "back to

Eve". Although it is also passed from female to male, the males

do not transmit it further.

While autosomal DNA comes equally from both parents, this is not

true of DNA as a whole. Not only does mtDNA come from the mother

only, but we will also see below that the Y chromosome is much

shorter than the X chromosome. Thus everyone inherits slightly

more DNA from the mother than from the father, and this is

particularly true for men.

The first exposure to DNA analysis for some readers may have been

the two-part Blood Of The Irish television documentary first

broadcast in 2008. The second part can be viewed on YouTube. The

genetic narrative jumps back and forth, without any explanation,

between Y-DNA and mtDNA. The climax of the programme was the

revelation that three children from a sample of unspecified size

from Carron and Kilnaboy in County Clare had similar mitochondrial

DNA to ancient remains found in a nearby cave, estimated to be

3,500 years old.

The objective of the programme may have been to investigate

whether the direct male line and direct female line ancestors

thousands of years ago of those living in Ireland today were men

and women who also lived in Ireland thousands of years ago.

However, much of the programme appeared to assume that this

desired conclusion had already been proven, and to extrapolate

from the direct male line and.direct female line ancestors to

the billions of other ancestors living at the same time.

There have been great scientific, technological and commercial

advances in the world of DNA analysis since 2008, but, even by the

standards of its time, this programme left much to be desired.

Tips for computer

programmers

If you are not a computer programmer or software developer, then

you may want to skip ahead to the next section

on mutation.

Traditional genealogy applications will produce pedigree charts

and descendancy charts for any individual in a GEDCOM file showing

respectively all the ancestors from whom the root individual may

have inherited autosomal DNA and all the descendants to whom the

root individual may have passed on autosomal DNA (and their

spouses). These charts were probably not designed with autosomal

DNA in mind. It is just coincidence that one can potentially

inherit autosomal DNA from all of one's ancestors, and that one

can potentially pass on autosomal DNA to all of one's descendants.

I am still looking for a genealogy application which will produce

similar pedigree charts and descendancy charts showing the

inheritance paths of the other three types of DNA. For example, an

X pedigree chart should show just the ancestors from whom the root

individual could have inherited segments of X-DNA and an X

descendancy chart should show just the individuals to whom the

root individual might have passed on segments of X-DNA.

Blank X descendancy charts are widely available, but software to

fill them in for specific individuals is hard to find.

It is surprising that even GEDmatch.com has not as of September

2014 implemented X pedigree charts.

Back in 1991, I wrote a program myself to produce descendancy

charts showing only descendants inheriting the Y chromosome from

the root individual, but it assumed the underlying database was in

the original PAF format and contained less than 32K individuals,

so is hardly worth resurrecting now (as PAF has been discontinued

and had switched to a new format before its discontinuation, and

as my own database is now several times that maximum size limit

and as it has become almost impossible to find a PASCAL compiler

for a modern computer).

My hope is that these charts can be most easily added to TNG which I use for my own

genealogy website. I have started a discussion of this topic in the TNG forums.

Programmers working on genealogy software may be interested in

the minor modifications to existing code required to provide these

options. A new variable with four possible values (Y, X, autosomal

[the current default] and mt) is required. Four cases must be

dealt with depending on the value of this new variable. The

default autosomal case remains unchanged, certainly if there is

already a choice as to whether spouses of descendants (who clearly

do not inherit the root individual's autosomal DNA) are included

or omitted. The other three cases are dealt with as follows:

- Y inheritance path

- For the pedigree chart, just follow the direct male line in a

single column format.

- For the descendancy chart, insert something along these lines:

-

IF descendant is female THEN

proceed to next descendant

ELSE {descendant is male}

output descendant

stack descendant's children for later processing

proceed to next descendant

- X inheritance path

- For the pedigree chart, insert something along these lines:

-

IF ancestor is female THEN

stack ancestor's father and mother for later processing

output ancestor

proceed to next ancestor

ELSE {ancestor is male}

stack ancestor's mother for later processing

output ancestor

proceed to next ancestor

- For the descendancy chart, insert something along these lines:

-

IF descendant is female THEN

output descendant

stack descendant's children for later processing

proceed to next descendant

ELSE {descendant is male}

output descendant

stack descendant's daughters for later processing

proceed to next descendant

- "Cascading" X-descendants charts would also be a nice feature,

i.e. going back generation by generation, a descendants chart

for each X-ancestor, showing those of his or her X-descendants

not yet shown on a previous X-descendants chart. The full set of

these cascading X-descendants charts would show all the cousins

with whom one could theoretically share X-DNA.

- It has been suggested

that Charting

Companion "can automatically color all your X-chromosome

ancestors in your Ancestor charts & Fan charts" although I

can find no mention of this on the product's own website.

Blaine

Bettinger has written an article on Unlocking

the

Genealogical Secrets of the X Chromosome in which he

includes nice colour-coded blank fan-style pedigree charts

showing the ancestors from whom men and women can potentially inherit X-DNA.

- mt inheritance path

- For the pedigree chart, just follow the direct female line in

a single column format.

- For the descendancy chart, insert something along these lines:

-

IF descendant is male THEN

output descendant

proceed to next descendant

ELSE {descendant is female}

output descendant

stack descendant's children for later processing

proceed to next descendant

Ann

Turner did this for the MS-DOS version of Personal

Ancestral File (PAF) away back in 1994.

The letters observed at each location on a child's genome are

typically inherited unchanged (other than by recombination) from

one or other parent.

A son inherits his Y chromosome and one set of 22 autosomes

virtually unchanged from his father and inherits his X chromosome,

his mitochondrial DNA and another set of 22 autosomes virtually

unchanged from his mother.

Similarly, a daughter inherits one X chromosome and one set of 22

autosomes virtually unchanged from her father and inherits her

mitochondrial DNA, another X chromosome and another set of 22

autosomes virtually unchanged from her mother.

However, isolated mutations, essentially just

transcription errors, can occur.

Mutation rates vary greatly along the human genome.

At most locations on the genome, the mutation rate is effectively

zero and the same letter is observed for all humans.

Some locations have a slightly greater mutation rate, in the

range of one mutation in the entire history of mankind. Such

locations on the Y-chromosome and in mitochondrial DNA are very

useful for slotting individuals into the appropriate locations on

the relevant evolutionary tree or phylogenetic tree. While

a great deal of effort has gone into identifying such locations,

they are not useful for practical genealogical purposes, as two

individuals with the same letters at a set of such locations may

still not have any common ancestor within thousands of years. By

2015, hopes were high that some surname-specific Y-DNA mutations

might soon be identified.

If locations have a higher mutation rate, perhaps as high as

1-in-20 or even 1-in-10 reproductions, then comparing the letters

observed at a set of such locations can have great genealogical

value. Two individuals with the same observations at a set of such

fast-mutating locations are very likely to have a relatively

recent common ancestor or common ancestral couple.

Estimation of the time to most recent common ancestral couple

depends crucially on both the number of locations compared and on

the estimated mutation rates for each of those locations, based on

research involving many parent/child observations.

There are two different basic units in which the length

of a segment of DNA is frequently measured, and a third unit used

only for the types of DNA which are subject to recombination,

namely autosomal DNA and X-DNA:

- base pair (bp)

- Each chromosome comprises two complementary strands of

DNA, known as the forward strand and the reverse

strand, and entwined in the shape of a double helix,

which looks like a twisting or rotating ladder. If the letters

in one of the complementary strands are known, then those in the

other can be deduced, since A can pair only with T and C can

pair only with G. A base pair, sometimes called a Watson-Crick

base pair, comprises a letter from the forward strand and

the corresponding letter from the reverse strand. So the value

of a base pair can be one of AT, TA, CG or GC. Similarly, for

example, the substring TTAACGGGGCCCTTTAAATTTAAACCCGGGTTT in one

strand must pair with the substring

AATTGCCCCGGGAAATTTAAATTTGGGCCCAAA in the other strand. For the

purposes of genetic genealogy, once the string of letters

representing the forward strand is known, the information in the

reverse strand is redundant. Nevertheless, the phrase base

pair is used as the fundamental unit in which the length

of a DNA segment is measured.

- Don't be confused by the fact that autosomal chromosomes come

in pairs (the paternal chromosome and the maternal

chromosome) and that each of these chromosomes in turn

contains two strands of DNA (the forward strand and the

reverse strand). Thus, one person's autosomal DNA

comprises 22 pairs of chromosomes, 44 chromosomes or 88 strands

of DNA. When comparing two people's autosomal DNA, one is

looking at 44 pairs of chromosomes, 88 chromsomes or 176 strands

of DNA.

- One thousand base pairs is a kilobase (kb) and one

million base pairs is a megabase (Mb).

- (The length in base pairs of the genome is referred to as the

physical map length.)

- single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)

- As already observed, the vast majority of the base pairs in

the genome of most humans are identical.

- A single-nucleotide polymorphism, abbreviated SNP

and pronounced snip, is a single location in the genome

where, due to mutations, there is a relatively high degree of

variation between different people.

- The word polymorphism comes from two ancient Greek roots,

"poly-" meaning "many" and "morph" meaning "shape"

(mathematicians reading this will be familiar with the notion of

isomorphism). Each of these roots can be somewhat misleading.

- In the context of a SNP, "many" misleadingly suggests "four",

but typically means "two", as only two of the four possible

letters are typically observed at any particular SNP. These

typical SNPs are said to be biallelic. Those rare SNPs

where three different letters have been found are said to be triallelic.

The word polyallelic is used to describe SNPs where

three or four different letters have been found. See Hodgkinson

and Eyre-Walker (2010). Polyallelic SNPs would be of

enormous value in genetic genealogy, but are rarely mentioned,

other than to acknowledge their existence. Why not?

- Furthermore, since the 1990s, the verb "morph" has appeared

in the English language with a meaning more akin to "change

shape". In this new sense of "morph", "polymorphic" misleadingly

suggests "fast-mutating". In fact, many SNPs are slow-mutating

rather than fast-mutating locations. As already noted, SNPs

where mutations are observed once in the history of mankind are

just as useful for their own purposes as SNPs with greater

mutation rates.

- Like both the propensity for recombination and the propensity

for mutation at individual SNPs, the density of SNPs which have

been identified varies markedly along the genome. Thus, when

looking at DNA which is subject to recombination (X-DNA and

autosomal DNA), the number of consecutive SNPs at which two

individuals match is of greater genealogical significance than

the total number of consecutive base pairs at which they match.

- The number of SNPs identified in a given segment can also vary

between companies, researchers or technologies. Specific SNPs

have been chosen for the Illumina chips as they are

ancestry-informative as distinct from medically informative.

- The SNPs which the DNA companies

examine are not necessarily all the SNPs. In other words, the

locations not examined are not necessarily locations at which

all humans are identical. Thus, it is possible that two people

match at a long sequence of consecutive observed SNPs, but that

there are unobserved SNPs between the observed SNPs at which the

two people do not match. Dave Nicolson

has written a

paper about this.

- centiMorgan (cM)

- Unlike the other two units of measurement, the centiMorgan is

applicable only to the types of DNA which are subject to

recombination, namely autosomal DNA and X-DNA. It can not be

used to measure Y-DNA or mtDNA.

- The propensity for recombination varies along each chromosome.

One can plot the estimated expected cumulative number of

crossovers or recombination events encountered so far against

the location (measured in base pairs) along each chromosome. The

expected number of crossovers encountered between two locations

can be read from the graph. The distance in centiMorgans

between the two locations is just this expected number divided

by 100. (The full unit, the Morgan, is no longer used.)

- As one recombination is expected every 100 centiMorgans, it

follows (because of a mathematical result known as Jensen's

Inequality) that the expected length of the typical segment of

DNA inherited by a child from a parent on a very long chromosome

would be just over 100 cM. Similarly, the expected length of the

typical segment inherited by a grandchild from a grandparent

(with two opportunities for recombination) would be of the order

of 50cM; for a greatgrandchild from a greatgrandparent, of the

order of 25cM, and so on. The next segment in each case will be

inherited from a different ancestor.

- As chromosomes are no longer than a couple of hundred

centiMorgans, segments are broken up by the end of a chromosome

almost as often as by a recombination event, so in practice

average segment lengths are shorter than suggested by the above

rule of thumb.

- If we assume that crossovers are statistically independent,

then it follows that recombination follows what statisticians

call a Poisson process. The number of crossovers in one

generation in a segment of DNA x centiMorgans long has a

Poisson probability distribution with parameter x/100.

The number of crossovers in n generations in a segment

of DNA x centiMorgans long has a Poisson probability

distribution with parameter n*x/100.

- For example, the probability of no crossover in 299.6cM is 5%.

This result is worth remembering, as it can be used in many

ways. If you share a segment of, say, 30.98 cM with another

randomly selected person, then you can deduce that there is only

a 5% probability that this segment has gone through ten or more

reproductions without recombination (since 299.6/30.98 is just

under 10). Equivalently, there is a 95% probability that you are

a fourth cousin or closer of the other person.

- Similarly, the probability of no crossover in 69.3cM is 50%.

- The abbreviation cM (with a capital M) is used to distinguish

the centiMorgan from the centimetre (abbreviated cm with a small

m).

- The number of base pairs to which a centiMorgan corresponds

varies widely across the genome because different regions of a

chromosome have different propensities towards crossover. These

expectations and propensities presumably come from experimental

data and change as more data is collected, so that the

definition of centiMorgan may also vary over time and between

DNA companies using different experimental data. The number of

base pairs per centiMorgan varies both from chromosome to

chromosome and within chromosomes. As can be calculated from the

table below, a centiMorgan in one part of chromosome 3 can be

under 800,000 base pairs, but a centiMorgan in one part of

chromosome 11 can be over 6,000,000 base pairs.

-

| CHROMOSOME |

START LOCATION |

END LOCATION |

LENGTH |

CENTIMORGANS |

| 1 |

44805958 |

47175419 |

2369461 |

1.08 |

| 2 |

106254302 |

116973471 |

10719169 |

8.09 |

| 2 |

157113214 |

159347591 |

2234377 |

2.44 |

| 3 |

11537627 |

12600665 |

1063038 |

1.41 |

| 4 |

165504024 |

167423895 |

1919871 |

2.29 |

| 6 |

29267608 |

31571470 |

2303862 |

1.53 |

| 11 |

46718718 |

56273717 |

9554999 |

1.54 |

| 11 |

103382220 |

105990699 |

2608479 |

2.38 |

| 17 |

36593956 |

38838321 |

2244365 |

1.92 |

- As can be seen from the above table, from the FTDNA

website, when no unit of measurement is specified, length

is apparently assumed to mean length in base pairs.

FamilyTreeDNA and GEDmatch use different centiMorgan

scales. Here's an extreme example from chromosome 9:

FTDNA: 9 81,628,878

90,218,677 18.04 2,500

GEDmatch: 9 81,369,061

90,503,719 13.2 2,433

In base pairs, the GEDmatch length is far longer than the

FTDNA length; but in centiMorgans, the GEDmatch length is far

shorter than the FTDNA length.

- (The length in centiMorgans of the genome is referred to as

the genetic map length.)

If a segment of X-DNA or autosomal DNA has lots of SNPs, then two

people's DNA is unlikely to be identical purely by chance on that

segment.

Conversely, if a segment is small in terms of centiMorgans, then

it wont have seen many recombinations over the generations, and

may have been inherited unchanged from a very distant ancestor,

particularly in the case of X-DNA which is not subject to

recombination when passed from father to daughter.

Thus, to be sure that a segment is inherited from a recent common

ancestor, one would like to see that it is long on both the

centiMorgan and SNP scales.

Given a long shared segement, unless we have a complete pedigree for

both parties going back many generations, it will always be

difficult to know whether the shared segment comes from a known

common ancestor or an unknown common ancestor on some other

ancestral line.

Converting between

units of measurement

There must be plots somewhere showing the monotonic relationship

between the length along each chromosome measured in base pairs,

the length along the chromosome measured in centiMorgans and the

length along the chromosome measured in SNPs, but I have not yet

come across them.

Genealogists are probably used to variables which can be measured

in either of two units of measurement which are linearly

related to each other. For example, those with nineteenth

century rural Irish ancestors will have converted the areas of

their ancestors' landholdings from the Irish acres

generally used in the Tithe Applotment Books to the statute

acres used in Griffith's Valuation using the fixed conversion

ratio 121 Irish acres=196 statute acres. A graph of areas in

Irish acres versus areas in statute acres will look like a

straight line.

For the three units of measurement in which DNA is measured,

there are no such fixed conversion ratios, as the relationships

between the units of measurement are non-linear. The local

conversion ratios between base pairs, centiMorgans and SNPs vary

considerably along the genome. Graphs of the relationship between

base pairs and centiMorgans or between base pairs and SNPs or

between centiMorgans and SNPs will slope upwards, but otherwise

will not look anything like a straight line.

In the absence of such representative graphs, the best that I can

show here is a table based on the local conversion ratios in a

(non-random) sample of 4,339 regions (those where I am half-identical with one or more of my 381

FTDNA-overall-matches as of 10 Jan 2014; by construction, this is

an unrepresentative sample). These may be biased estimates of the

average conversion ratios throughout the genome.

|

bp/cM |

bp/SNP |

SNP/cM |

| Minimum |

112,200 |

118 |

89 |

| Average |

1,413,219 |

2,292 |

331 |

| Maximum |

10,576,336 |

18,786 |

2,384 |

Each of the measurement units defined above

can also be converted into percentages of the total length of the

genome, which are a much simpler way of viewing the results for

autosomal DNA and X-DNA, which both come in segments from multiple

ancestors.

The use of percentages assumes that a precise value of the total

(the denominator in the percentage calculation) is known.

The total length of the human genome in base pairs is

typically imprecisely specified as "over 3 billion DNA base pairs"

(see table in Wikipedia).

This

total length, however, includes only one copy of each of the 22

autosomal chromosomes. The genome actually contains around 6

billion base pairs, as it contains two copies of each autosomal

chromosome. James Michael Connor (Medical Genetics for the

MRCOG and Beyond, RCOG, 2005, page

3) confirms, for example, that there are "280Mb in each copy

of chromosome 1", so that the base pairs figures in the Wikipedia

table clearly represent the numbers of base pairs in one copy of

each autosomal chromosome. Gianpiero

Cavalleri confirms that, roughly speaking, "Each of us

inherits 6 billion letters of DNA, 3 billion from our mother and 3

billion from our father."

Since it is common to speak about the length of DNA, the width

of the human genome can correspondingly be viewed as two base

pairs for the autosomal chromosomes and for a woman's X

chromosomes; elsewhere it can be viewed as one base pair wide. The

following table summarises the details:

|

Male |

Female |

|

Length |

Width |

Total |

Length |

Width |

Total |

| Autosomal |

2,881,033,286 |

2 |

5,762,066,572 |

2,881,033,286 |

2 |

5,762,066,572 |

| X |

155,270,560 |

1 |

155,270,560 |

155,270,560 |

2 |

310,541,120 |

| Y |

59,373,566 |

1 |

59,373,566 |

|

|

0 |

| Mitochondrial |

16,569 |

1 |

16,569 |

16,569 |

1 |

16,569 |

| GRAND TOTAL |

3,095,693,981 |

|

5,976,727,267 |

3,036,320,415 |

|

6,072,624,261 |

Note that the X chromosome contains almost three times as many

base pairs as the Y chromosome, so the total number of base pairs

in the female human genome is greater than the total number of

base pairs in the male human genome.

Despite this confusion about the total length of the genome, the

base pair remains the most precise and unambiguous of the three

units of measurement; however, it is also the least appropriate as

a measure of the genealogical relevance of a shared segment of

DNA.

The total number of cM is also imprecisely specified, apparently

varying slightly from one DNA website to another. Figures for the

length in cM of the autosomal chromosomes only and figures for the

length in cM of the autosomal chromosomes and the X chromosome

combined may be seen and should not be confused. Furthermore, the

definition of the centiMorgan is based on empirical observation of

recombination frequencies, and thus can vary based on the

particular experimental data on which it is based.

The total number of SNPs used by a particular DNA company is at

least directly observable in the raw data downloadable from the

company. For example, my raw autosomal DNA data from

FamilyTreeDNA.com includes precisely 696,752 SNPs, with one letter

from my paternal chromosome and one letter from my maternal

chromosome observed at each SNP. My raw X-DNA data includes one

letter from each of precisely 17,797 SNPs. If I were female, then

I would have another letter from my second X chromosome at each of

these 17,797 SNPs. As with centiMorgans, the definition of SNPs is

based on empirical observation of variation, and thus can also

vary based on the particular experimental data on which it is

based and on the DNA company collecting the data. A location where

no variation is observed in a small sample may exhibit variation

in a larger sample and be reclassified as a SNP. DNA observation

is also subject to measurement error, so there will be occasional

SNPs which result in no calls

so that there can be slight variation in the number of SNPs

observed between different individuals even with the same DNA

company.

For all these reasons, it is critically important to avoid

ambiguity by giving precise details of how the centiMorgan or the

SNP has been defined, including specifying the full length of the

genome and its components according to the relevant definition.

One way of getting a feel for the length of your autosomes in

SNPs and cMs is to do a one-to-one comparison of your own kit with

your own kit at GEDmatch.com.

This table shows my details:

| Chr |

End Location |

Centimorgans (cM) |

SNPs |

bp/cM |

bp/SNP |

SNP/cM |

| 1 |

247,169,190 |

281.5 |

57,186 |

878,043 |

4,322 |

203 |

| 2 |

242,683,192 |

263.7 |

55,850 |

920,300 |

4,345 |

212 |

| 3 |

199,310,226 |

224.2 |

45,709 |

888,984 |

4,360 |

204 |

| 4 |

191,140,682 |

214.5 |

39,248 |

891,099 |

4,870 |

183 |

| 5 |

180,623,543 |

209.3 |

40,685 |

862,989 |

4,440 |

194 |

| 6 |

170,732,528 |

194.1 |

46,476 |

879,611 |

3,674 |

239 |

| 7 |

158,811,958 |

187.0 |

36,759 |

849,262 |

4,320 |

197 |

| 8 |

146,255,887 |

169.2 |

35,757 |

864,396 |

4,090 |

211 |

| 9 |

140,147,760 |

167.2 |

31,717 |

838,204 |

4,419 |

190 |

| 10 |

135,297,961 |

174.1 |

37,783 |

777,128 |

3,581 |

217 |

| 11 |

134,436,845 |

161.1 |

35,392 |

834,493 |

3,799 |

220 |

| 12 |

132,276,195 |

176.0 |

34,384 |

751,569 |

3,847 |

195 |

| 13 |

114,108,121 |

131.9 |

26,933 |

865,111 |

4,237 |

204 |

| 14 |

106,345,097 |

125.2 |

22,630 |

849,402 |

4,699 |

181 |

| 15 |

100,214,895 |

132.4 |

21,052 |

756,910 |

4,760 |

159 |

| 16 |

88,668,978 |

133.8 |

22,030 |

662,698 |

4,025 |

165 |

| 17 |

78,637,198 |

137.3 |

19,564 |

572,740 |

4,019 |

142 |

| 18 |

76,112,951 |

129.5 |

21,052 |

587,745 |

3,615 |

163 |

| 19 |

63,776,118 |

111.1 |

14,454 |

574,042 |

4,412 |

130 |

| 20 |

62,374,274 |

114.8 |

17,887 |

543,330 |

3,487 |

156 |

| 21 |

46,909,175 |

70.1 |

9,948 |

669,175 |

4,715 |

142 |

| 22 |

49,528,625 |

79.1 |

10,112 |

626,152 |

4,898 |

128 |

| All autosomes |

2,865,561,399 |

3587.1 |

682,608 |

798,852 |

4,198 |

190 |

The End Location column may understate the chromosome lengths in

bps, as it probably refers to the location of the last SNP on the

chromosome, and there may several thousand more bps beyond that

last SNP.

Note that the variation in the overall ratios between the

different units of measurement from one chromosome to another is

small compared to the variation between smaller segments

illustrated in an earlier table and that the various ratios are

very different from those in the earlier unrepresentative sample.

While the length in centiMorgans of each chromosome appears to be

the same from one FTDNA customer to another, the number of SNPs

observed on every chromosome varies from customer to customer and

the end locations can also vary in some cases.

Note that for each of the chromosomes, the probability of

recombination is greater than 50%, ranging from 50.4% for

Chromosome 21 to 94.0% for Chromosome 1. Conversely, the

probability of inheriting an entire chromosome intact from one

grandparent ranges from 6.0% for Chromosome 1 to 49.6% for

Chromosome 21.

Although in theory the chromosomes are numbered in order of

decreasing length, this is not the case in the table, where

Chromosome 22 is longer on all three scales than Chromosome 21.

Observing DNA

It is neither practical nor essential nor affordable to observe

all 6,072,624,261 base pairs in the female human genome, as the

vast majority of these have the same value for all women, and

similarly for men.

Instead we just observe the locations which are known to vary

from one person to another.

In the case of autosomal DNA, FTDNA makes observations at 696,752

paternal SNPs and at the corresponding 696,752 maternal SNPs.

For each of the 696,752 locations, two letters are observed, say

A and G, but it is not possible to tell whether the A comes from

the paternal copy of the relevant chromosome and the G from the

maternal copy, or vice versa.

Presumably if we moved along the genome observing every letter

along the way we could keep track of which were the paternal

letters and which were the maternal letters; instead, we pop in

just once every 4000 or so base pairs, at which stage we can no

longer look back and see which is the paternal chromosome and

which the maternal chromosome.

In other words, instead of observing 696,752 ordered pairs

of letters (of which there are 16 possible values, namely any one

of ACGT with any one of ACGT: AA, AC, AG, AT, CA, CC, CG, CT, GA,

GC, GG, GT, TA, TC, TG and TT), since the parental source of the

letters can not be observed, we observe 696,752 unordered

pairs (of which there are ten possible values: AA, CC, GG,

TT, AC, AG, AT, CG, CT and GT).

In other words, observed autosomal DNA is represented not by two

(unobservable) ordered strings of letters, but by one array of

unordered pairs of letters.

The observed unordered data is said to be unphased; the unobservered

ordered data which we would like to have is said to be phased. There are various

limited techniques available for phasing

the unordered data. A certain amount of simple phasing of a

child's data is possible if samples are available from both of the

child's parents. Ancestry.com uses more sophisticated phasing

algorithms, particularly in the new matching process which it

introduced in November 2014.

I took an interest in equine pedigrees from a very young age,

even before I began to be interested in human pedigrees. I have

long taken an interest in the activities of Equinome, a

University College Dublin campus company which claims to have

identified a SNP called the speed gene which predicts a

racehorse's distance perference. It was only when I realised that

the unordered pairs observed at the location of Equinome's speed

gene can be C:C, C:T and T:T that I realised the vast difference

between the two possible A-with-T and C-with-G base pairs in a

single chromosome and the ten possible unordered pairs observed in

maternal and paternal chromosome pairs.

A region is a run of unordered pairs, starting at one

specified locus on a specific chromosome and ending at another

specified locus on the same chromosome. In theory, the region

comprises one DNA segment on the paternal copy of the chromosome

and another DNA segment on the maternal copy of the same

chromosome. In practice, neither of these segments is

independently observed.

Comparing W's DNA and Z's DNA in theory

Consider the comparison between person W's DNA and person Z's DNA

in a particular region on a particular chromosome. (Since the

mathematician's usual generic variables X and Y refer to

chromosomes in genetics, I'll try to avoid confusion by using V, W

and Z instead as variables to denote generic people.)

If we could observe W's paternal segment, W's maternal segment,

Z's paternal segment and Z's maternal segment in this region, then

we could tell whether or not one of W's segments was identical

to one of Z's segments. If we found two matching segments, then we

could state that these segments were identical by

state (IBS) and that W and Z segment-match on

this segment.

Provided that W's paternal segment is different from W's maternal

segment and likewise Z's paternal segment is different from Z's

maternal segment, then we can start to investigate whether these

IBS segments are identical by descent (IBD).

If

- there is a proven family tree connecting W to Z via a common

ancestor;

- we also have DNA samples from the relevant ancestors of W and

Z back to their most recent common ancestor (MRCA)

and from the spouses of those ancestors; and

- the IBS segment matches only one spouse at each generation

back to the MRCA,

then we have proven that the matching segments are IBD. The term

IBD is often loosely used when this level of rigorous proof is

lacking.

Even if no DNA samples are available for some of the people on

the family tree, it may still be possible to prove that the

matching segments are IBD.

More generally, the unavailablility of some DNA samples means

that we can merely draw conclusions about the likelihood

of a hypothesised relationship given the DNA or, equivalently, the

probability of the observed DNA given the hypothesised

relationship.

In general, the longer two IBS segments, the more likely they are

to be IBD.

Since we do not independently observe W's paternal segment, W's

maternal segment, Z's paternal segment and Z's maternal segment in

the region of interest, we must base comparisons on the unordered

pairs that we do observe.

Think of W as yourself and Z as another person who has been

selected at random from a DNA database.

Let us first consider a particular location or SNP.

At this single location, W's unordered pair matches Z's unordered

pair if it is possible that one of W's unobservable segments

matches one of Z's unobservable segments. In other words, they

match if at least one letter is common to both pairs.

Things could get confusing here, as we are comparing two people,

each of whom has a pair of letters at every point on the

chromosome. Remember that pair refers to the two letters,

not to the two people.

For example, at a biallelic SNP, where either A or G can be

observed on each chromosome, the unordered pairs which can be

observed are AA, AG and GG.

- If W is AG, then W automatically matches Z, whether Z is AA,

AG or GG.

- If W is AA, then W matches Z provided that Z is not GG.

- Conversely, if W is GG, then W matches Z provided that Z is

not AA.

To avoid the confusion which would arise if the word 'match' was

used in multiple different senses, we say that unordered pairs

which match in this sense are half-identical pairs and if

their pairs are half-identical, we say that W is

half-identical to Z at this location.

A person whose paternal and maternal letters are the same at a

particular location (AA, CC, GG or TT) is said to be homozygous

(or homozygotic) at that location. A person whose paternal and

maternal letters are different at a particular location (e.g. AC)

is said to be heterozygous (or heterozygotic) at this

location.

At locations which are biallelic (the vast majority), someone who

is heterozygous will automatically be half-identical to everyone.

Thus, observing a heterozygous pair provides no information

whatsoever about the possibility that the two people are related.

All the relevant information comes from locations at which both W

and Z are homozygous, and the few locations which are polyallelic.

If W and Z are homozygous at a particular location, but with

different letters (e.g. W is AA and Z is GG), then they clearly

did not inherit that location from a common ancestor.

However, if W and Z are homozygous at a particular location with

the same latter (e.g. both W and Z are AA), then they may have

inherited their autosomal DNA at that location from a common

ancestor.

When investigating the possibility of a relationship, we can

discard any biallelic SNPs at which either W or Z is heterozygous,

since those SNPs provide no information about the likelihood of a

relationship. We just need to compare the locations at which both

W and Z are homozygous, i.e. their mutually homozygous

locations.

The more consecutive mutually homozygous locations we find, the

more likely it is that the relevant region includes a segment of

DNA inherited from a common ancestor.

To explore the probabilities involved, let us suppose that the

SNP we are considering is biallelic with the proportions p

and 1-p of the population having each value, say A and C

respectively, and correspondingly, assuming independence of

paternal and maternal letters, the proportions p2,

2p(1-p) and (1-p)2 of the population

having each unordered pair, say AA, AC and CC respectively.

If you are homozygous AA at that SNP, then the other person is

half-identical to you unless he or she is CC, in other words

half-identical with probability 1-(1-p)(1-p)=2p-p2=p(2-p).

Similarly, if you are homozygous CC, then the other person is

half-identical to you with probability 1-p2.